Warning: spoilers ahead.

Watching the new Apple TV+ Idris Elba vehicle “Hijack,” the philosophy of the show is clear: If you’re on a hijacked plane, don’t make a fuss.

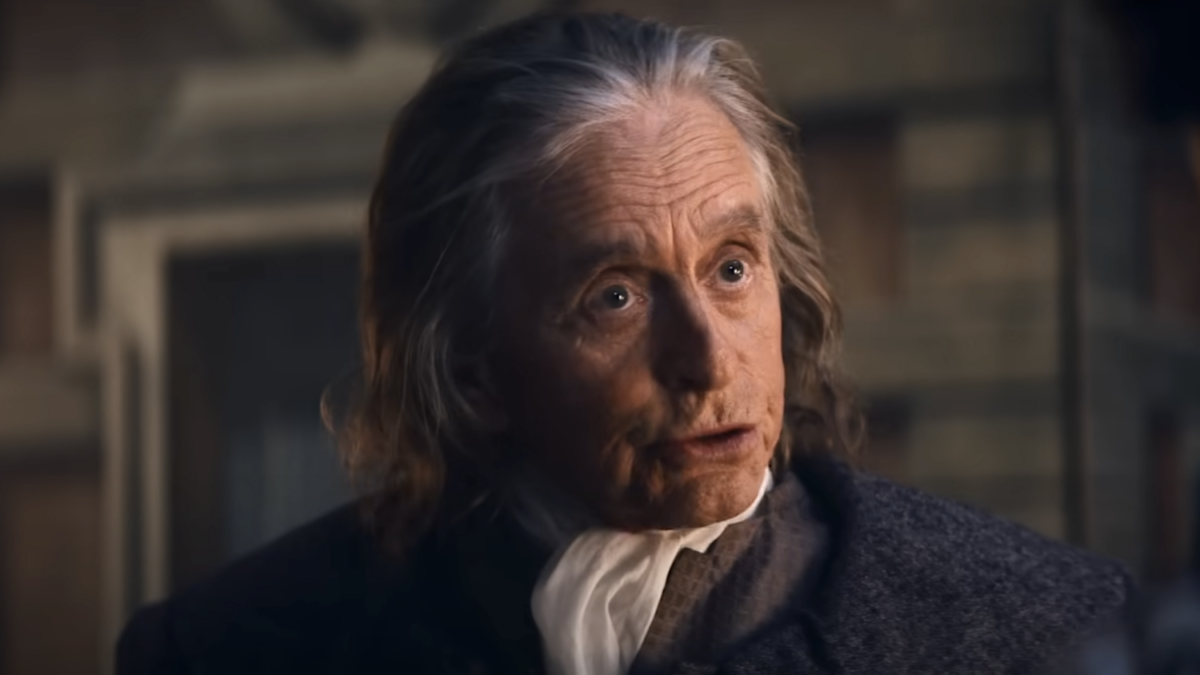

In this seven-episode show about an Airbus A330 full of mostly British passengers en route from Dubai to London, Sam Nelson (Idris Elba) focuses all his considerable talent as a corporate negotiator not on fighting a small gang of hijackers but on facilitating their efforts, because, you see, “I just want to get home to my family.”

To that end, he makes helpful suggestions to the hijackers, aids them in their efforts to manage the passengers, placates their anger, sympathizes with their personal crises, and actively discourages resistance. He literally hands a hijacker’s gun back to him. By the end, he’s made it progressively less likely that he or anyone else will get home — this despite (without giving too much away) learning early on that for a very specific reason, resisting the hijackers with force stands a very good chance of success.

Watching at our house, we were literally left shouting at Elba and the apparently super-glued-to-their-seats passengers: “Do something!”

It all works out to be a perfect illustration of a certain evolved mindset toward criminals: “Please don’t make them angry; fighting back will only make things worse. It’s best if we just cooperate and help them along their way.”

I don’t know if it says something about the European mindset toward criminality or not, but the truth is there are more than 200 passengers aboard this aircraft and only five hijackers thinly spread between several compartments. It’s hard not to imagine that a handful of ordinary American 4-H kids would have routed these scalawags in the first 20 minutes and been home to work on their county fair projects by now.

But that would have prevented the show from unrolling episode by episode as a master class in Too Clever by Half.

Of course, that is not the intent of the show. Throughout the message seems to have been that thinking people need not and should not resort to brutish resistance. In fact, the two passengers (50-ish white males, naturally) who are eager to oppose the hijackers in the “Let’s roll” mode are quickly identified and easily defeated. They spend the rest of the show tied up and impotent as Elba’s character launches his schemes, each making the situation worse than the last.

There’s one howler where Elba’s character saves a hijacker with a bad chest injury using a makeshift chest tube. The producers were apparently under the impression that such a thing is used to breathe through rather than merely to release lung-collapsing pressure in the chest cavity. They seem to have confused it with the emergency tactic of using the empty tube of a ballpoint pen to establish an airway for a choking person.

Why it would be a good thing to save the life of a hijacker anyway is unclear.

Meanwhile, politicians handling the crisis on the ground squabble about whether the hijackers are “terrorists” or merely “criminals,” with a recognizably smug and uncompromising conservative (50-ish white male, again, naturally) easily outwitted by criminals. This hard-line advocate is later revealed as irresolute and cowardly. Surprise.

It’s all so boringly predictable, not to mention unhappily reminiscent of blue-jurisdiction urban areas where leftists enact their notions of criminal justice and community activism.

In American cities like Indianapolis, a Democrat mayor launches endless community peace initiatives that are of interest only to already peaceful people, while every morning the news details the previous day’s shootings. The city-county council in July passed his “aspirational” gun control package promising to make the city free of “assault weapons” and permitless and concealed carry — if the state legislature allows it. (It won’t, not that the criminals shooting people would observe the new rules anyway.)

The previous Republican administration’s signs urging residents to “call to report illegal panhandling” are still in place but seem to be unenforced. Beggars are a constant presence squatting on the median at many major intersections.

Indianapolis is no Seattle or San Francisco, but there has been an undeniable decline in the quality of life in the central core. We have relatives who were repeatedly verbally assaulted by a street person as they dined at an outside restaurant downtown. Such experiences are not uncommon.

It’s not coincidental that, just as in many blue jurisdiction urban areas, the police department struggles to maintain effective numbers and recruit new officers. In Indy and other Democrat-controlled cities — where declining police forces and administrations are determined to endlessly invent new and creative ways to avoid acknowledging real problems, never mind effectively address them — a crash seems inevitable. And when it comes, it’s likely to require tragic levels of violence to restore order, when judiciously applied force much earlier on would have sufficed.

A catastrophic crash also seems inevitable as Elba’s jetliner loses altitude over London in the series finale, and it’s hard not to look back over the previous episodes and identify any number of points at which the use of force could have ended the crisis. This, though, would have required Elba’s character and others to fully acknowledge the truth of their situation and take steps to end it, rather than hoping that reasoning with the hijackers and easing their path would bring them back into the fold of decent behavior.

Despite the fact that this approach has an abysmal and bloody track record, Elba seems to have gone into the project explicitly determined to give it full play. He has been quoted elsewhere as saying about his character, “I didn’t want to play the tough guy, or the hero. … I wanted him to be quite weak and fragile.”

Now that’s genuinely toxic masculinity, and it doesn’t bring peace; it invites violent aggression.