It has been a strange and wonderful thing to watch Apple TV-Plus become an unassuming home for great historical content. While its science-fiction shows flounder, its dramas go unappreciated, its “Peanuts” specials go ignored, and its breakout series “Ted Lasso” having concluded, the Apple-backed streaming service has found a modest business producing much of the finest historical content in recent memory.

Whether it’s the Tom Hanks-backed WWII productions “Greyhound” or “Masters of the Air,” the excellent Civil War drama “Manhunt,” the contrarian documentary “Lincoln’s Dilemma,” or auteur epics like “Napoleon” and “Killers of the Flower Moon,” Apple TV-Plus has shown its willingness to throw massive sums at history series for a niche crowd of enthusiasts.

The newest of these is “Franklin,” a miniseries from former HBO chairman Richard Plepler and screenwriter Kirk Ellis, who both helped develop the “John Adams” miniseries. Borrowing from their prior experience adapting the popular David McCullough book into a vehicle for one of Paul Giamatti’s greatest performances, this newest series adapts Stacy Schiff’s A Great Improvisation: Franklin, France, and the Birth of America into an eight-episode political drama — which just had its finale on May 17.

The series has thus far gone relatively ignored in the wider pop culture, a victim of the oversaturation of the streaming economy. However, the nominal reception it has received has been relatively lukewarm to negative. Its Rotten Tomatoes audience rating is 52 percent, with mainstream critics being mixed — some calling it “crackling,” “addictive,” “nuanced,” and “beautifully textured,” and others calling it “clunky,” “apathetic,” “poorly focused,” “exhausting” and “mind-numbing.”

There is truth to the criticisms. “Franklin’s” creators haven’t made the “John Adams” lightning strike twice, nor are they likely to in the post-1619 Project or post-“Hamilton” world. However, a drama about Benjamin Franklin is naturally going to involve eccentricity. Being the oldest and wisest of the Founding Fathers, he was the elder statesman of the American Revolution, and his involvement in the war involved a great deal of backdoor dealmaking and lurid drama. In these regards, “Franklin” works.

The series is set against the American Revolution, charting the years Franklin served in France as an unofficial ambassador to the United States, as he attempts to curry favor among the elites and draw England’s hated enemy into the war.

The core idea the series plays with is the complexity of diplomacy, and this is something Benjamin Franklin is uniquely well and poorly suited to. He’s an international celebrity, a renowned scientist, and the living embodiment of the New World. He’s a sage, a libertine, and a journalist, with an adept understanding of the French people. He’s also beloved by those around him, highly aware of his fame and eager to take advantage of the game of politics for personal gain. He’s able to be funny on command, while still portraying some of the endemic earthiness and grit essential to the early American soul, compared to the elegance of the aristocracy.

These factors place his arrival in France as a great source of drama and intrigue, as he proves remarkably adept at playing the games necessary to advance in the decadent world of 1770s France.

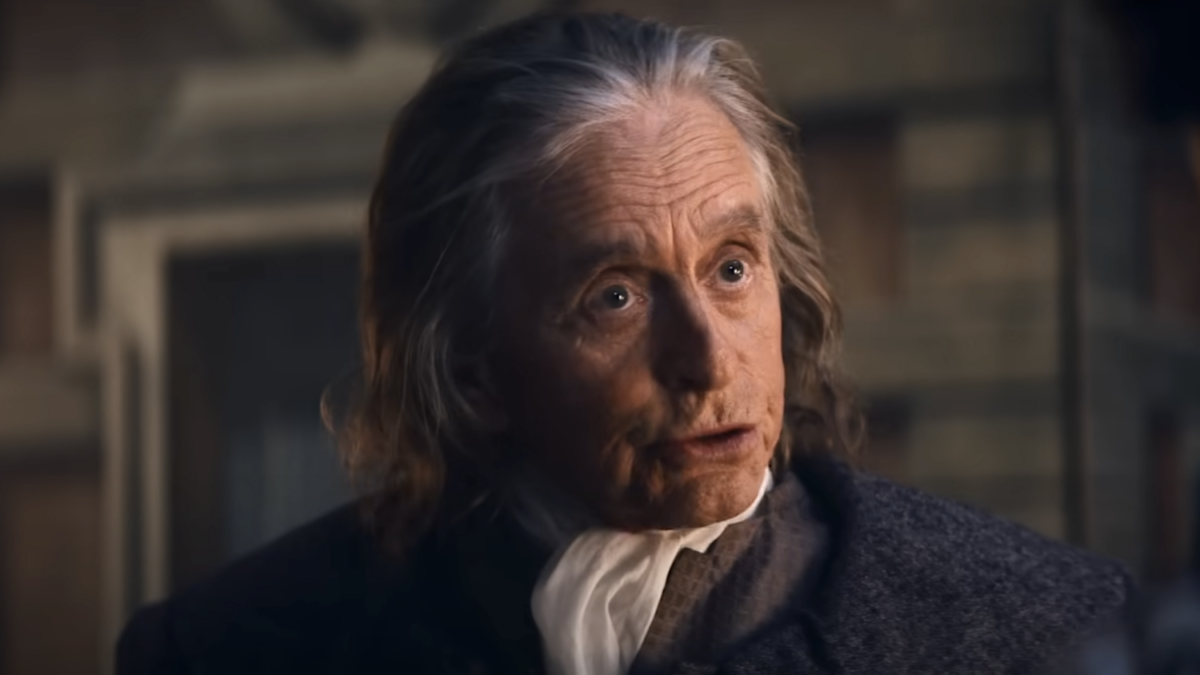

Michael Douglas shows up to play the titular role, but his portrayal of Franklin is more of a concoction than an embodiment of the character. His version of Franklin is acerbic, witty, smooth, sexually liberated, and kindly, particularly regarding his grandfatherly relationship with his grandson, Temple. But whereas Howard da Silva disappeared into the role in “1776,” Douglas creates his version of Franklin that is compelling, multidimensional, and inauthentic.

Given that the series is set over nearly a decade, the plot’s progress grinds to a halt at points, while its main characters struggle to move it forward. Temple has his own coming-of-age story in the background that keeps him busy, while Franklin is grappling with nosy police, British spies, selfish aristocrats, and a French king who is weary of betting on the outcome of the war in a manner that would harm the monarchy (and ultimately does). This is a story of long-term maneuvering, with characters having complex motivations and cynical actors constantly attempting to head off one another, to seemingly little effect. This crawling plot is somewhat purposeful, given that Franklin himself affirms that this is his tactic to make progress with the French court, but it makes for messy television plotting.

Thankfully, Eddie Marsan’s John Adams appears in the back half of the series and adds an extra layer of drama to the proceedings as the numerous threads and conflicts converge. Much like in the “John Adams” miniseries, which covers these events in one-eighth the screentime, Adams is clueless about how to address the French diplomats and has differing priorities from Franklin, whose libertine sexual activities disgust him. Others descend upon him in this manner and try to take advantage of those disagreements to sow division.

There’s certainly much to recommend with “Franklin,” despite that it appeals to a fairly narrow audience. Speaking for myself, there aren’t many shows or movies about the Revolutionary War. What comes to mind are “The Patriot,” “Drums Along the Mohawk,” “1776,” “John Adams,” “Hamilton,” and a handful of low-budget television shows and silent movies. “Franklin,” though certainly quiet and flawed, stands out to me, as there simply aren’t many contemporary retellings about this valuable time of history. It is easy to forgive something rare.