2023 will go down in history as the year that China’s state-sponsored hackers advanced their ability to wage cyber warfare against the U.S.

Chinese hackers used to focus on stealing America’s commercial secrets and personnel information (see examples here and here). But this year, Chinese hackers have expanded their reach by collecting intelligence on U.S. government agencies and breaching systems of infrastructures with strategic value.

In May 2023, The New York Times reported that a Chinese state-sponsored hacking group had installed malware in electric grids in Guam and other parts of the U.S. since February 2023, probably seeking to cut off power to the U.S. military in case China invades Taiwan.

Microsoft disclosed in July that China-based hackers “gained access to email accounts affecting approximately 25 organizations in the public cloud, including government agencies as well as related consumer accounts of individuals,” since May 15, 2023. The affected government agencies included the U.S. State Department. U.S. national security officials identified the hackers as affiliated with Chinese intelligence. Google Cloud’s Mandiant senior vice president and chief technical officer, Charles Carmakal, called Chinese hackers’ techniques “very advanced.”

Cyber Warfare Reaches U.S. Infrastructure

Then, last week, DailyMail.com reported that Chinese hackers affiliated with the People’s Liberation Army have gained access to essential infrastructure sites in the U.S., including a water utility in Hawaii, a major port, and at least one oil and gas pipeline. The hackers’ access to the water utility in Hawaii is probably of the utmost concern since the U.S. Pacific fleet resides near the island of Oahu. Chinese hackers had been “sitting on a stockpile of strategic vulnerabilities” without being detected for almost a year.

Brandon Wales of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency said, “It is very clear that Chinese attempts to compromise critical infrastructure are in part to pre-position themselves to be able to disrupt or destroy that critical infrastructure in the event of a conflict.”

For example, if the Chinese Communist Party invades Taiwan, Chinese military-affiliated hackers will likely disrupt critical infrastructure in the United States. Wales said the hackers will try “either to prevent the United States from being able to project power into Asia or to cause societal chaos inside the United States — to affect our decision-making around a crisis.”

China’s Vulnerability Database

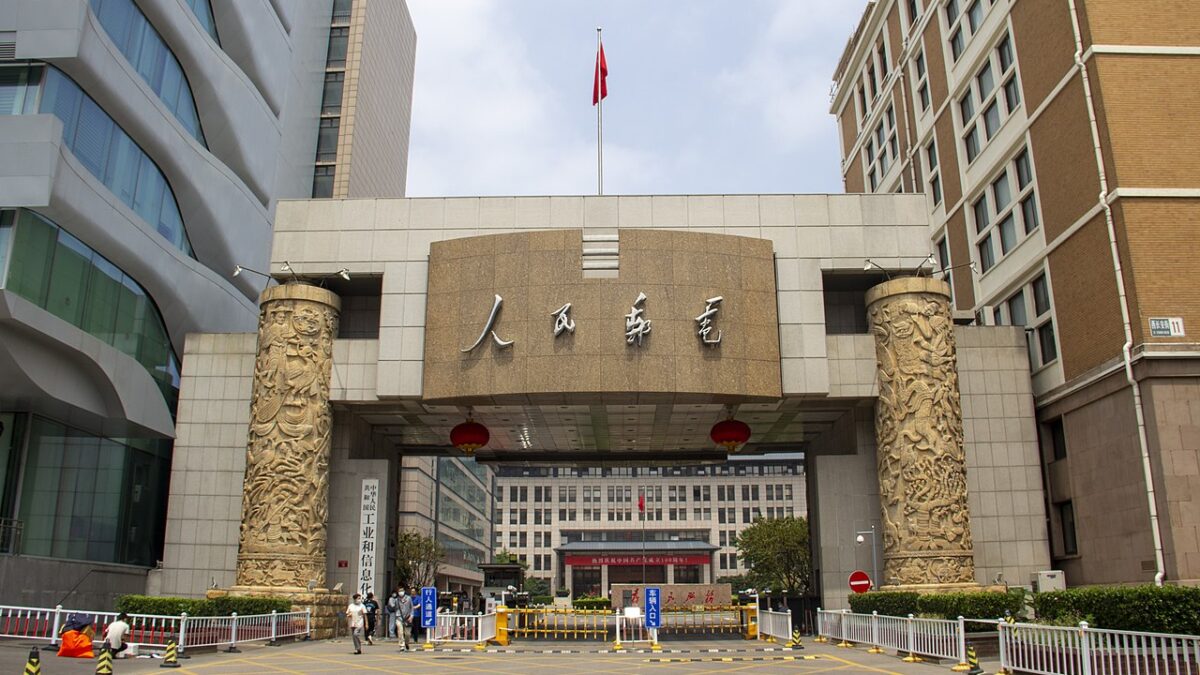

China’s state-sponsored hackers are relentless, and they have received the state’s assistance to enhance their abilities. For example, Beijing passed a Data Security Law in 2021. It includes a provision that requires technology companies doing business in China to report their software vulnerabilities to China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) within 48 hours after the issue became known. The MIIT then adds such vulnerabilities to a National Vulnerability Database and generates vulnerability reports.

The Chinese government claims such a database and its reports are necessary for researchers to learn how to fix those software vulnerabilities and enhance cybersecurity. Beijing omitted to mention that MIIT shares its software vulnerability reports with other Chinese government agencies. These include China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS), the nation’s leading spy agency.

MSS’s activities include performing domestic counterintelligence, gathering foreign intelligence, conducting overseas influence campaigns, and organizing hacking. Last year, the U.S. Justice Department charged 13 individuals, including a few members of MSS, for “alleged efforts to unlawfully exert influence in the United States for the benefit of the government of the PRC.” The agency was also behind some of the most disruptive overseas hacking operations in recent years.

Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the security firm Beijing Topsec, two entities known for working with the PLA to carry out hacking campaigns, also have access to MIIT’s vulnerability reports.

A Head Start for Chinese Hackers

Another serious concern of this Chinese law is that it mandates companies to disclose any software vulnerabilities within two days of discovery, even though the average time it takes to patch its software flaws is between 60 days and more than 200 days.

Brad Williams, writing for Breaking Defense, warned that China’s new law essentially has given its state-sponsored hackers a head start. It provides them with “nearly exclusive early access to a steady stream of zero-day vulnerabilities” of software used by other countries, including the U.S. The law gives Chinese hackers plenty of time to exploit those vulnerabilities and advance their hacking abilities.

How many American companies have complied with China’s software vulnerability reporting mandate is unclear. Williams named two U.S. companies, Amazon Web Services and Microsoft, which have business operations in China and likely must comply with the software vulnerability disclosure requirement.

Unfortunately, both companies also have a significant presence in both the public and private sectors in the U.S. Their compliance with Chinese law could “potentially include those discovered in technologies used by the Defense Department and Intelligence Community” in the U.S. Even “a mere description of a bug with the required level of specificity would provide a ‘lead’ for China’s offensive hackers as they search for new vulnerabilities to exploit,” according to WIRED magazine.

China’s Cyber Warfare an ‘Active’ Threat

It is not a coincidence that since Beijing enacted mandatory software vulnerability reporting, China’s hackers have demonstrated an enhanced ability to breach into more strategically sensitive systems in the West, especially in the U.S. The Director of National Intelligence’s 2023 Annual Threat Assessment states, “China probably currently represents the broadest, most active, and persistent cyber espionage threat to U.S. Government and private-sector networks.”

The PLA has every intention to incorporate cyber warfare as part of its war planning against Taiwan and its allies. Foreign technology companies in China have a decision to make: Will they continue chasing short-term profits and market access in China, even if it means sharing software vulnerabilities? Or should they pack up and leave the hostile legal environment in China? Their decision will affect not only their own data security and that of their customers but also the national security of their homeland and allies.