The disturbing signs that North Korea’s dictator, Kim Jong Un, may be preparing for war are too many to ignore.

It all began in November. Kim Jong Un claimed that his country successfully launched a spy satellite into space on Nov. 21 and any interference with its satellite would constitute a declaration of war. South Korea responded by launching its own spy satellite and partially suspending an agreement about military cooperation with North Korea. Kim retaliated by announcing he would withdraw from all measures “taken to prevent military conflict in all spheres, including ground, sea, and air.”

Since then, the hostile rhetoric and proactive actions by North Korea against South Korea have intensified. Kim told his subordinates at the end-of-year policy meeting that he needed to “make a decisive policy change” because “the two Koreas were belligerent states at war, not counterparts for reconciliation and unification.” He also warned that “it is fait accompli that a war can break out anytime on the Korean peninsula.”

Kim followed up his rhetoric with action. On Jan. 5, North Korea fired more than 200 artillery shells at South Korea’s Yeonpyeong Island. The island, about two miles from the disputed maritime border in the Yellow Sea, is home to a South Korean military base. Fortunately, no one on the island was injured.

Following the shelling, Kim announced that his country would rewrite its constitution to label South Korea as its “No. 1 enemy,” and a peaceful reunification between the North and the South was no longer possible. Instead, the North would classify the South as a “hostile” foreign state, “one that constitutionally should be occupied, subjugated, and reclaimed in the event of war.” To show that he meant business, Kim ordered the abolishment of three government agencies working on inter-Korean affairs and tore down a reunification arch that had been built by his father, Kim Jong Il.

Longtime observers of the Korean Peninsula pointed out that Kim Jong Un’s rhetoric and actions this time were different from the regime’s typical rodomontade. Instead, Kim is signaling that he is abandoning a decades-long policy of seeking “peaceful reunification.” In an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal, John Bolton, a national security adviser under former President Trump, pointed out, “Mr. Kim’s belligerence and constitutional changes are bell ringers, the strongest possible signals of his intentions.”

Robert L. Carlin, who participated in U.S.-North Korea negotiations, and Siegfried S. Hecker, a professor of practice at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, recently warned, “The situation on the Korean Peninsula is more dangerous than it has been at any time since early June 1950. … We believe that, like his grandfather in 1950, Kim Jong Un has made a strategic decision to go to war.” Other observers don’t see a full-blown war in the Korean Peninsula anytime soon but suspect a limited military strike by the North is in the cards. Either way, decades of relative peace in the Korean Peninsula are now in jeopardy.

Why Kim Is Threatening War

There are several reasons why Kim may be more willing to take military action against South Korea. First, Kim probably received encouragement from Russian President Vladimir Putin. The relationship between the two nations has grown closer in recent years. Kim’s first overseas trip since the Covid-19 pandemic was a meeting with Putin last year. North Korea reportedly supplied ammunition to help Russia fight Ukraine. As the Russia-Ukraine war has become a stalemate, Putin probably hopes that Kim’s provocative rhetoric and actions about starting a war will divert the United States’ support for Ukraine.

From this perspective, Putin follows the same playbook once used by his predecessor, the Soviet Union’s Joseph Stalin. Stalin agreed to let Kim’s grandfather, Kim Il Sung, invade South Korea in 1950, hoping the Korean War would draw U.S. attention and resources away from the Cold War in Europe.

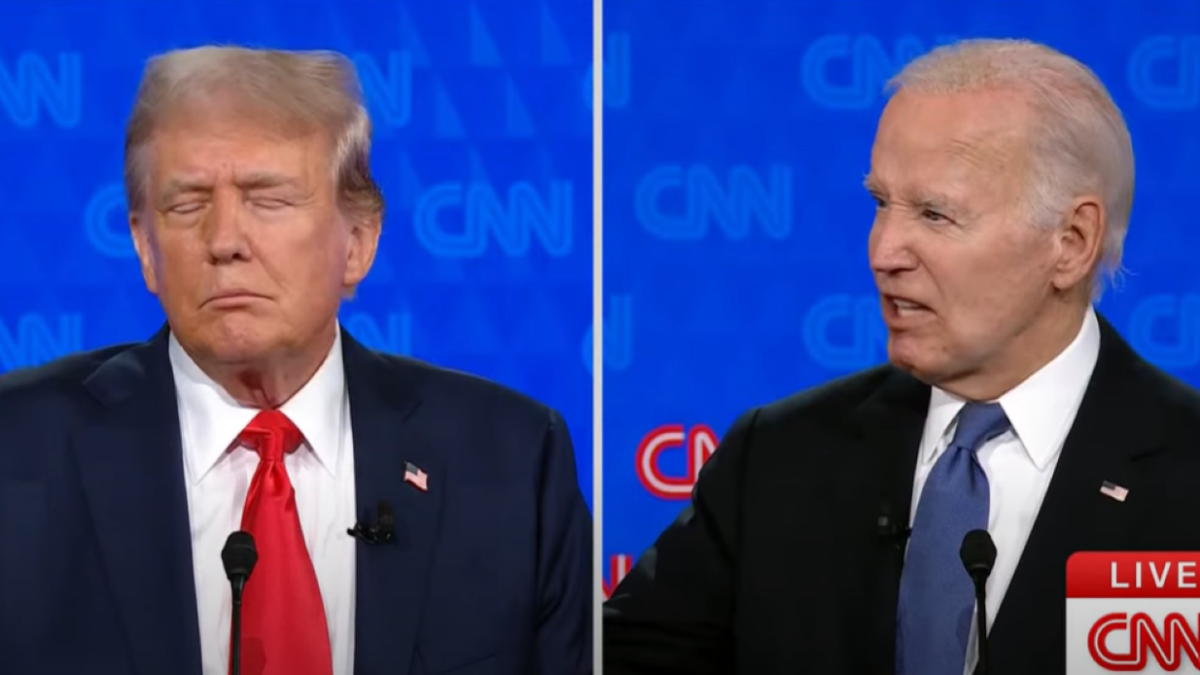

The second reason Kim may want to start a war is that he sees a window of opportunity in the Biden administration’s weak foreign policy and worldwide unrest. The Biden administration’s humiliating withdrawal from Afghanistan has emboldened America’s adversaries. The Russia-Ukraine war has depleted some U.S. military ammunition, which has caused the U.S. difficulty in arming its allies, such as Taiwan.

Additionally, as Bolton pointed out, “While Ukraine wasn’t overrun, it is far from being victorious, thereby proving to the world that the West will tolerate unprovoked aggression.” A case in point: Yemen’s Iran-backed Houthi rebels are stepping up their strikes on ships through the Red Sea and forcing the U.S. military to respond. Domestically, the Biden administration is further distracted by an upcoming election. Kim probably believes the best time to take military action is when the Biden administration is overwhelmed and preoccupied.

Last but not least, Kim probably feels confident in North Korea’s progress in weapon development. Carlin and Hecker, two long-term observers of North Korea, believe that “North Korea has a large nuclear arsenal, by our estimate of potentially 50 or 60 warheads deliverable on missiles that can reach all of South Korea, virtually all of Japan (including Okinawa), and Guam.”

North Korea’s state media also claimed last week that it carried out a test of its “underwater nuclear weapons system, which could carry a nuclear weapon.” Kim probably learned from Russia’s Putin that having nuclear weapons is his best insurance policy. He can take aggressive military action, while the United States and its allies have to restrain their response due to concerns about possibly triggering a nuclear war.

China’s Role

Just like in the 1950s, Kim Jong Un’s timing of military aggression against the South will depend on whether he has China’s support. Unlike Putin, China’s Xi Jinping probably is not eager for Kim to take any military action, which will complicate Xi’s plan for invading Taiwan. Still, history offers some clues about what Xi will eventually do.

Back in 1950, Mao Zedong initially didn’t support Kim Il Sung’s planned invasion of the South, precisely because Mao was getting ready to conquer Taiwan and eliminate his Nationalist Party rival. Mao didn’t want Kim’s action to draw the American military to China’s northeastern border with North Korea. Eventually, Mao decided to support Kim Il Sung because he knew that even without China’s support, Kim Il Sung probably would have invaded the South and brought the U.S. military to China’s doorstep anyway, threatening Mao’s new communist regime. Additionally, Mao saw China’s military involvement in the Korean War as an opportunity to eliminate former Nationalist troops who surrendered to the Communists during China’s Civil War (1945–1949) while enhancing his prestige in the international socialist camp.

Fast forward to 2024. As Xi gears up his military actions against Taiwan, he probably is not enthusiastic about Kim Jong Un drawing the U.S. military’s attention to China’s northeastern border. But just like Mao, Xi will support North Korea no matter what in order to keep it as a strategic buffer between China, the United States, and its allies. If Kim’s military actions weaken the United States in some way, it will only enhance Xi’s chance of invading Taiwan.

No one knows whether Kim Jong Un is planning a limited military action or a full-blown war. But we are sure that weakness invites aggression, the Biden administration’s policies have bolstered our adversaries, and the world is becoming more dangerous.